(Click here for Walter Ferro’s Career Chronology)

“Walter Ferro is among a small group of American woodcut artists whose work in both monochrome and color is beginning to invade editorial and advertising pages of major magazines still largely dominated by photography and full-color illustration.”

—William Caxton Jr., “The Woodcuts of Walter Ferro,” American Artist, 1962, p2.

“Working with engraving tools on these mellow blocks made an addict of me, and I have been a passionate follower of the woodblock ever since.”

—Walter Ferro, about his first engagement with the medium in 1950, as told in a 1971 interview with a newspaper in New Canaan, CT.

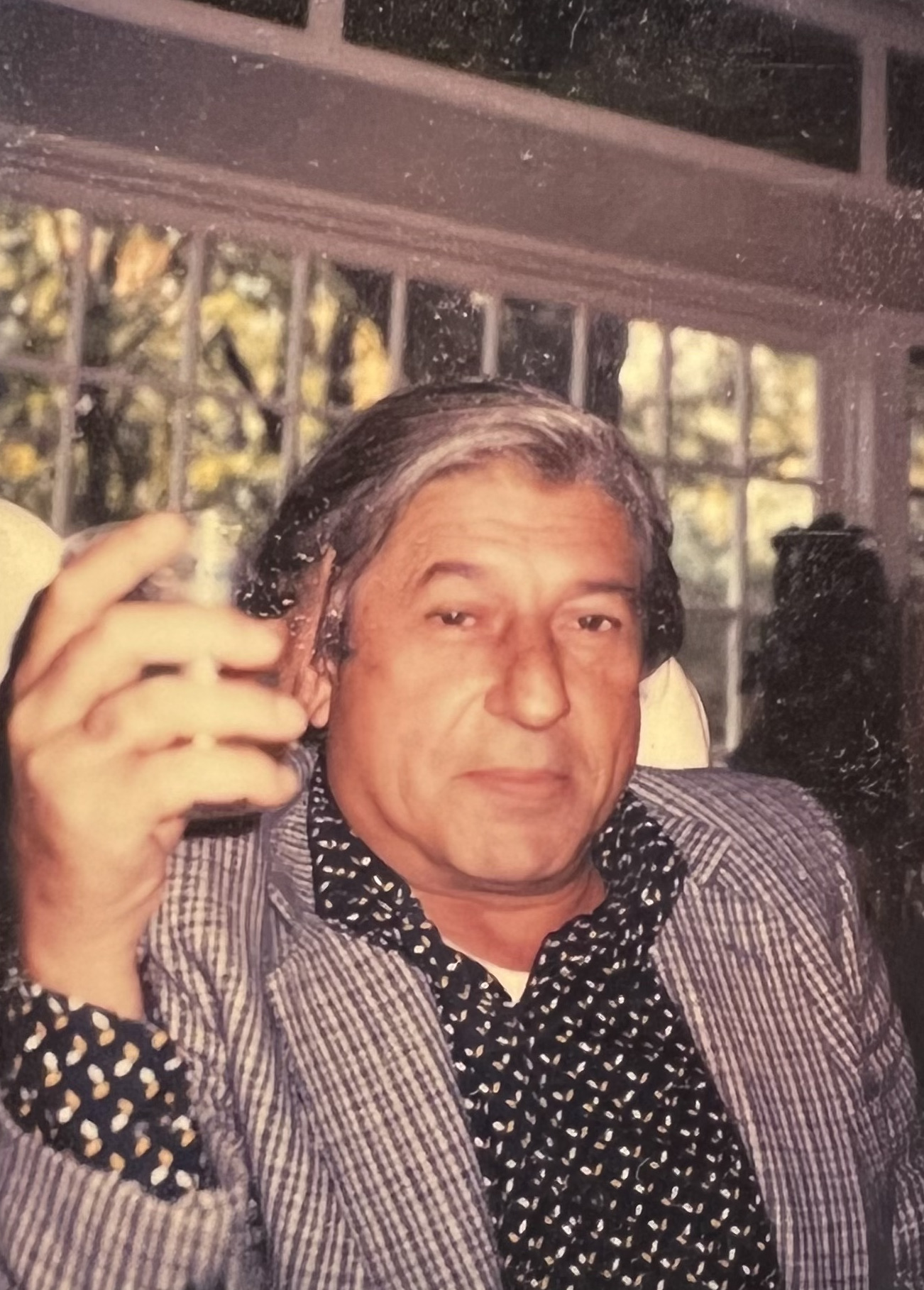

Born in 1925 in Brooklyn, New York, Walter Ferro began making art early, winning the John Wanamaker Gold Medal for a New York City-wide student art competition at the age of 12. He later studied at the Art Students League (1946-1948), and then from 1948 to 1952 at the Brooklyn Museum Art School in its heyday with American artist John Ferren. From this early interest Ferro went on to become a woodcut artist, illustrator, and designer, part of a small group of 20th Century American artists devoted to reviving the woodcut process in an era primarily concerned with other media, crafting material-laborious prints, as well as watercolors, collages, drawings, and public sculptures.

Receiving numerous awards including a Guggenheim Fellowship (1972) and exhibiting widely, Ferro had a passion, detail, and creative realism that remain both timeless and relevant today.

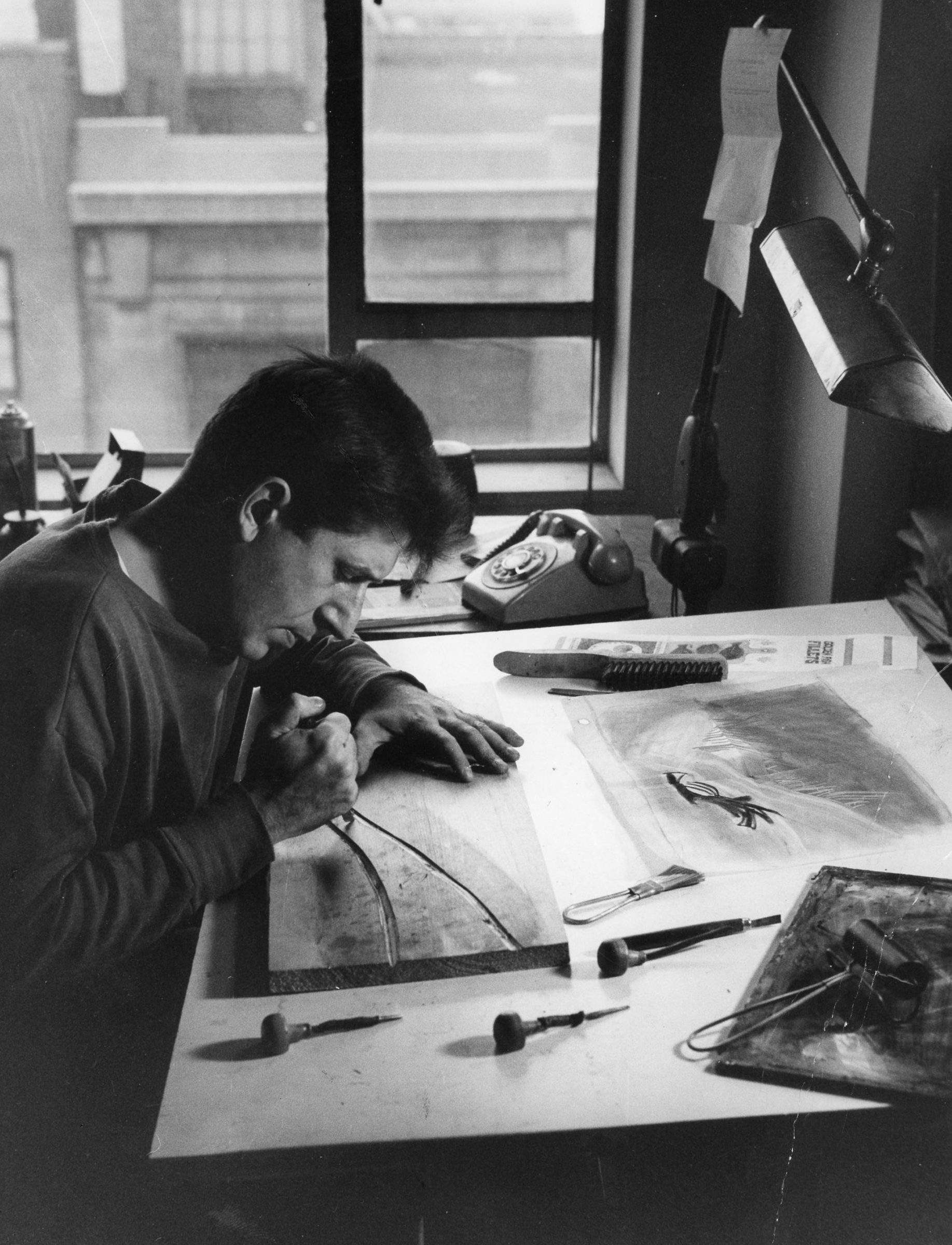

It was while an art director for an advertising agency in New York in 1950 that he first began engraving, initially in monochrome and later in color woodcuts, on “fine old Turkish boxwood blocks that had been resurfaced more than 50 years” earlier (interview, New Canaan, 1971). The process would become a primary focus for which he would garner much attention.

A scene designer for the Clare Tree Major Summer Theatre in New York (from 1947-1951), Ferro eventually freelanced as a designer, illustrator, graphic artist, and art director, working with projects and clients as wide-ranging as TIME, The New Yorker, Saturday Evening Post, Gourmet Magazine, Woman’s Day, and corporate clients such as IBM and Mobil Oil. He created woodcut illustrations for numerous publishers, including Random House’s edition of the ancient classic, The Heroic Deeds of Beowulf (1962), as well as for the first editions of Elie Wiesel’s Night (1958) and of Hemingway’s The Nick Adams Stories (1972), and designed many books, including for MIT Press, among others. In total he completed multiple illustrations and design projects for nearly 50 publishing, magazine, and corporate clients.

Of his time after art school and in his first years “as a one man art department” art director before freelancing, learning “everything from retouching to finished art and past-ups,” Ferro wrote:

“I became interested in wood engravings and read every book I could lay my hands on. Norman Kent’s “The Relief Print” was of particular help, because it detailed the actual methods of people like Lewis, Mueller, Landacre and Eichenberg.

I have never formally studied woodcutting with anyone. I located some old Harper’s wood blocks (Turkish end grain) which had been resurfaced. I used a spoon to print with. I found a proof press on Beekman Street…I have since gone back to the spoon for plank woodcuts.

The beauty of box wood and the sensation of cutting a design onto it can make an addict of any artist.” (Excerpt from Ferro’s 1969 application for Guggenheim Fellowship).

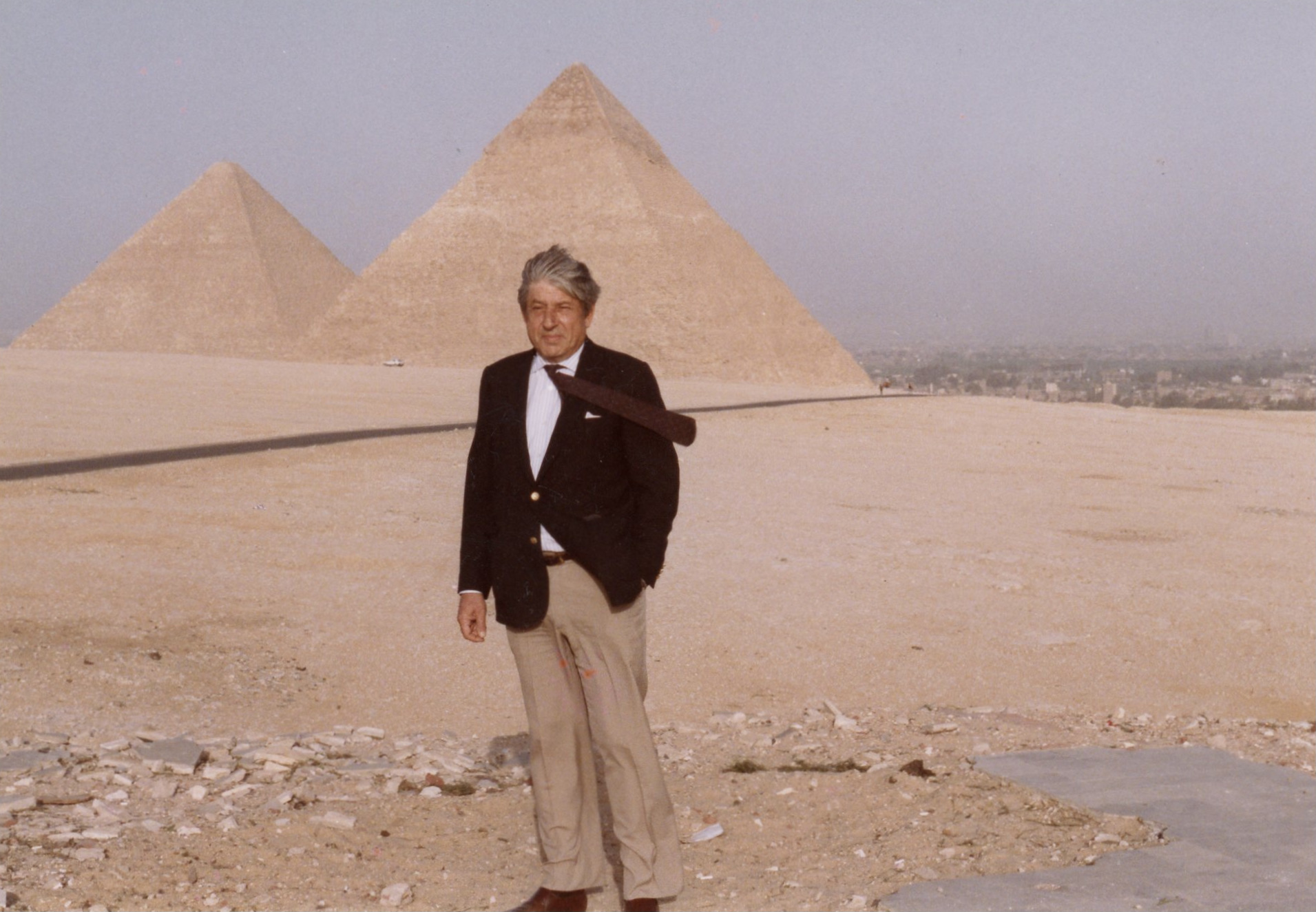

This spirit of curiosity, intellect, and adventure led him to pursue many varied interests, which translated into an expansive range of works and projects that brought him from North America to both Europe and the Middle East.

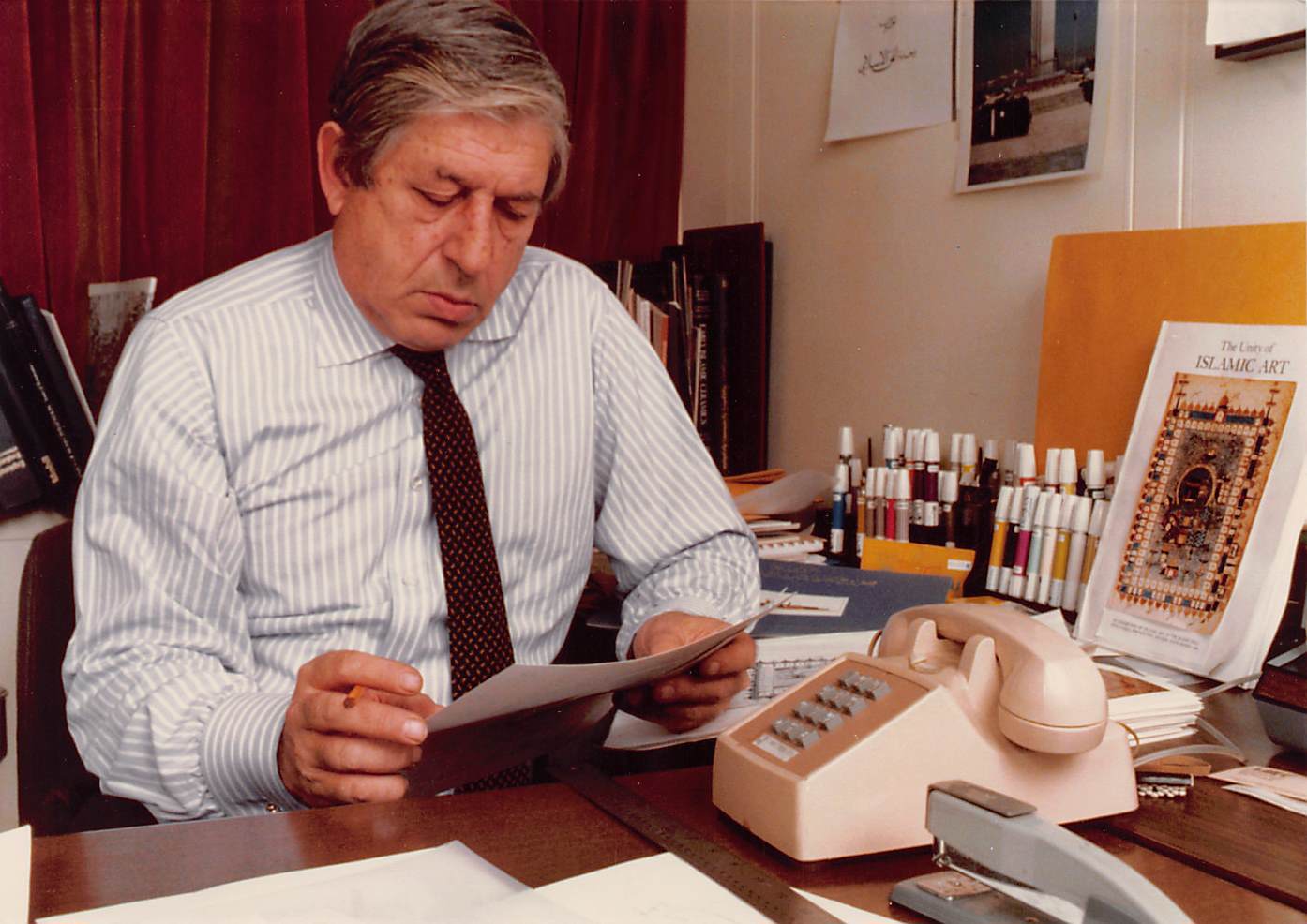

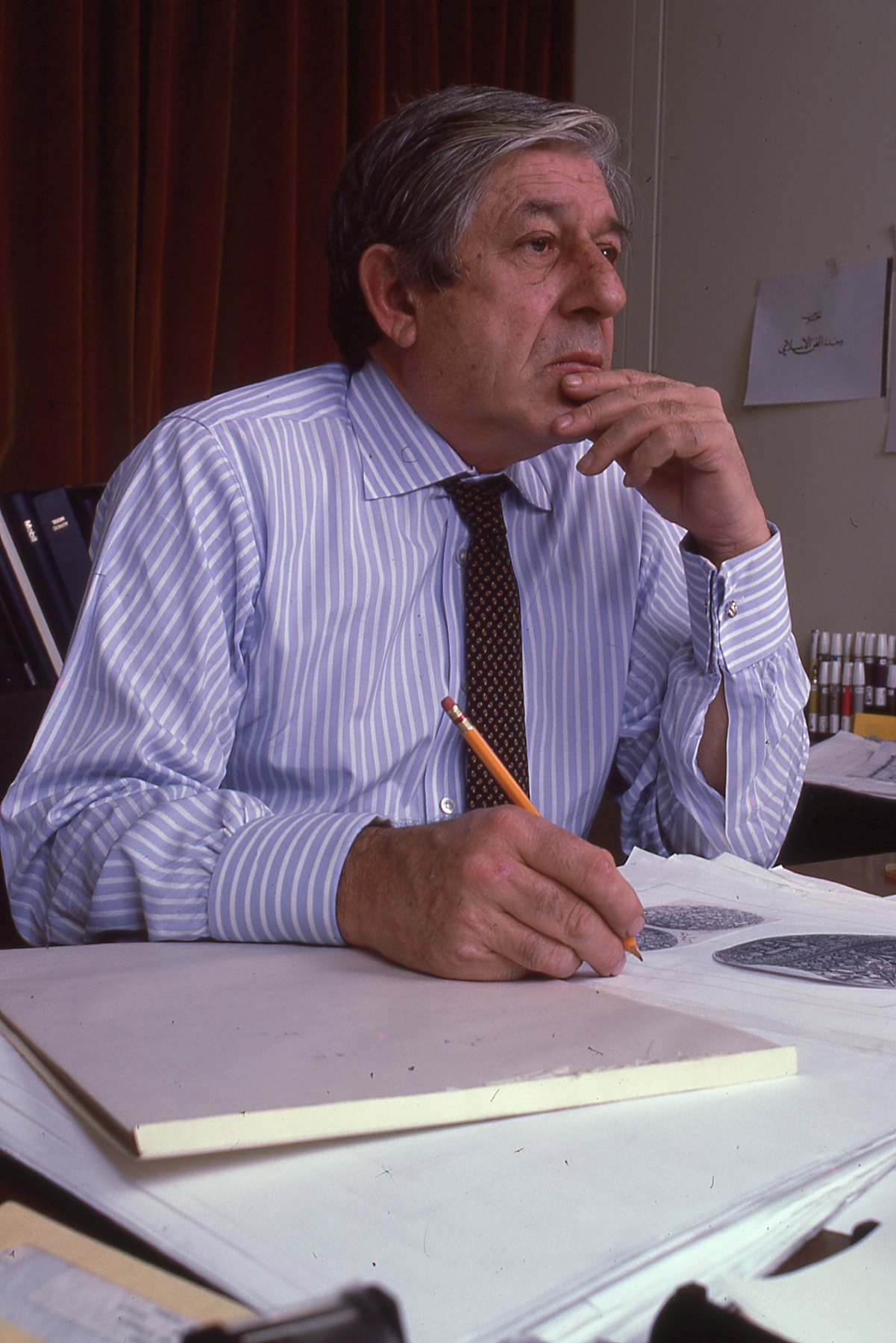

During a tenure from 1956-1966 as art director for the magazine Aramco World, he developed an interest and following in the Arab-world and in Middle Eastern art forms, which expanded into other projects. “I came up with a design to hinge a book at the top and then copy tracks through with Arabic on one side, English on the other, and with illustrations in the center,” he noted of his unique print techniques for Mobil’s English-Arabic publications (The Monthly Newsletter of the Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia, April 1984). Solar Clock, a monumental public art work and functioning clock commissioned by Mobil Oil and created from Ferro’s woodcut print of the same title, still stands today in a square in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Ferro’s designs for the book The Genius of Arab Civilization (New York University Press, 1975) also emerged from this time. In 1985 Ferro designed The Unity of Islamic Art, a significant book in conjunction with an exhibition at The King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies, in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

In the winter of 1969 – 1970, Ferro went to West Germany to prepare his application for the Guggenheim Fellowship, which he received and completed in 1972. Living in the hill town of Oberursel, west of Frankfurt, Ferro traveled through the surrounding satellite towns of the Taunus Mountains, stopping to paint watercolors along roads and in villages. The time offered him the opportunity to absorb and record the impressions of his new surroundings through numerous watercolor “seed impressions,” meant to be translated later into color woodcuts. Completed onsite wherever he was, without preliminary drawings underneath nor subsequent additions thereafter, these plein air watercolors offer an uninhibited expression of what he viewed, and a record of his glimpses of West Germany in that era. In 1990, over two decades later, this work caught the attention and interest of the local historical society in Oberursel, and Ferro returned to exhibit these watercolors, as well as additional newer works, in a solo exhibition at Galerie L9.

During his Guggenheim Fellowship, in 1972, Ferro embarked on a series of mixed-media collages, which included not only his beloved woodcut process, but also expanded to incorporate watercolor, gouache, cut and torn paper, tape, canvas, oil paint, and other items, including in at least one work, a corn husk. They exist as some of his most free form and experimental works. Alongside the collage experiments he also completed an array of other woodcuts and watercolors consistent with the artistic voice that he had developed by then, and continued to explore thereafter, for decades. (Transcriptions of Walter’s Writings leading to and during his Guggenheim Fellowship are available here.)

Ferro’s work resides in numerous collections, including among others those of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian Museum, and the Library of Congress.

From idyllic images of the seaside created for Audubon, to the solar clock for a market in Saudi Arabia, to iconic illustrations for first editions of classic authors, among many other works, Ferro approached a wide span of subjects and styles with equal attentiveness and charm. It is the intent of his family and estate to continue to bring his many works into the light, so that his creative talents can be viewed and appreciated by a new generation of audiences as diverse as the works themselves.

Curatorial Footnote:

Of particular consideration for future exhibitions of Walter Ferro’s work would be individuals and institutions specializing and/or interested in the niches that Walter cultivated over his lifetime: 20th Century woodcut and engraving processes in the revivalist movement in illustration; book, magazine, and other print illustrations crafted in analogue prior to or existing alongside the emergence of new computer technologies; 1980s American engagement with the Middle East and specifically Saudi Arabia; shifting depictions of priests and religious symbols in illustration and print over the 20th Century; artists featured in the American Artist magazine during its tenure; previous Guggenheim Fellows or students from the Brooklyn Museum’s Brooklyn Museum School of Art (which ran from 1890 – 1980) or Art Students League; woodcut and watercolor works of naturalist landscapes depicting ocean sides, as well as rural and village scenes (including farms and agriculture, sunflowers, towns, canals, and seascapes) in the United States and Europe, mid-late 20th Century, among others.